FROM CHAINS TO CHANGE

Bringing to life the convict origins of Australia’s labour movement.

Lens first covered the grand transnational history project Conviction Politics back in 2019, when Monash University’s Associate Professor Tony Moore, a leader of the project, was awarded a $757,000 government grant to further its answering of core Australian questions: “Who are we?” “Why are we like this?” CHRIS JOHNSTON reports.

Yesterday, Conviction Politics launched its centrepiece – an online multimedia hub that’s home to short documentaries, long and short textual reads, archive images, songs, and data visualisations.

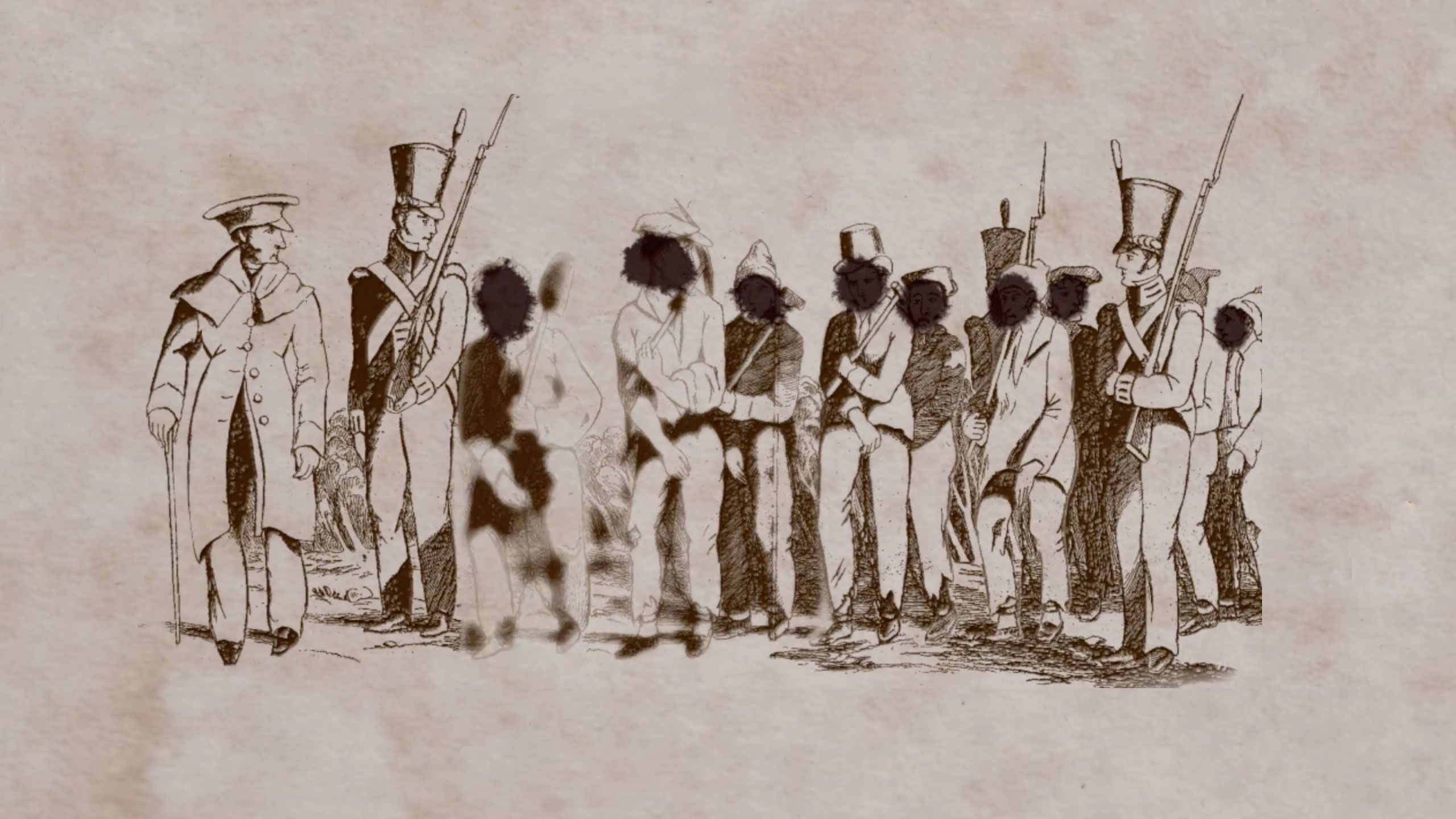

The documentaries – each about six minutes long – use a mixture of animation, interviews, live action and music performances to show the impact of the largely unknown activists and freedom fighters who made up good numbers of English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh convicts to Australia, together with Indigenous resistors from throughout the British Empire.

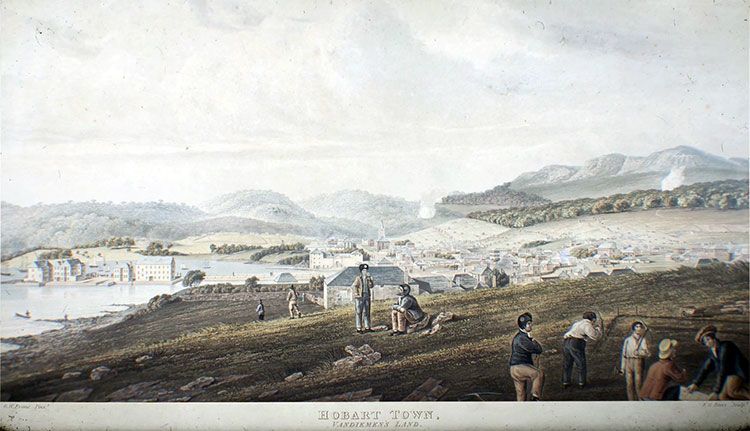

Hobart Town – Van Diemen’s Land, R.G. Reeve, 1828. (Source: National Library of Australia)

Hobart Town – Van Diemen’s Land, R.G. Reeve, 1828. (Source: National Library of Australia)

It shows how Britain’s Australian colonies – beginning as some of the most unfree and unequal jurisdictions on Earth – became some of the first places to give all working men the vote by the 1850s, and in quick time earned a reputation as the social laboratory of the world.

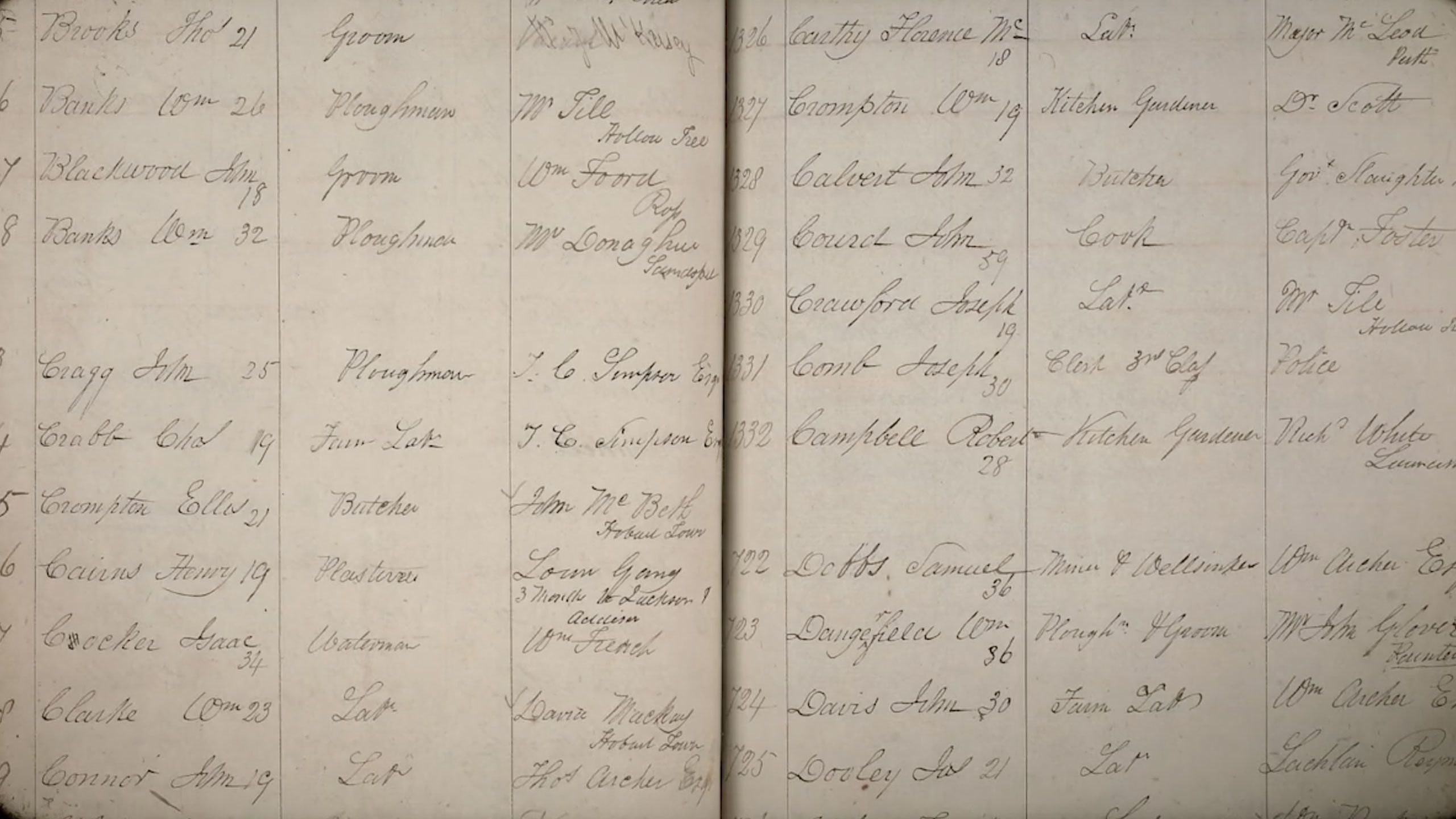

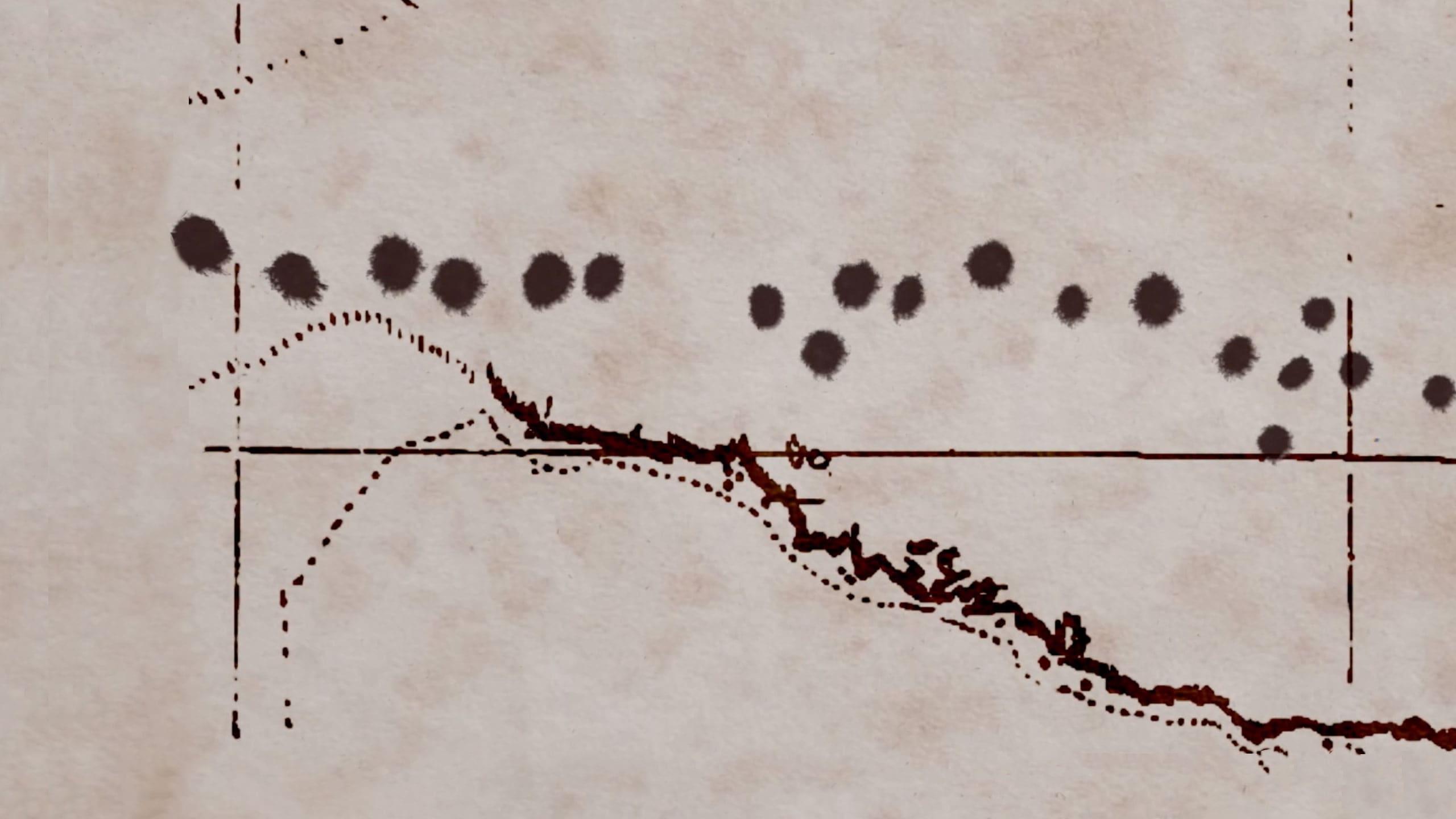

It uses newly digitised convict records, including those in the Tasmanian archives held by Libraries Tasmania, revealing unlikely victories around human rights and workers’ rights by Britain’s reformers and radicals who had been sent to Australia as punishment for activism back home.

It’s an extension of Associate Professor Moore’s book and documentary series of 2015, Death or Liberty.

The international project analyses convict records, colonial newspapers and activists’ own media to map patterns of political resistance by these “transported” men and women against exploitation of their labour and harsh conditions.

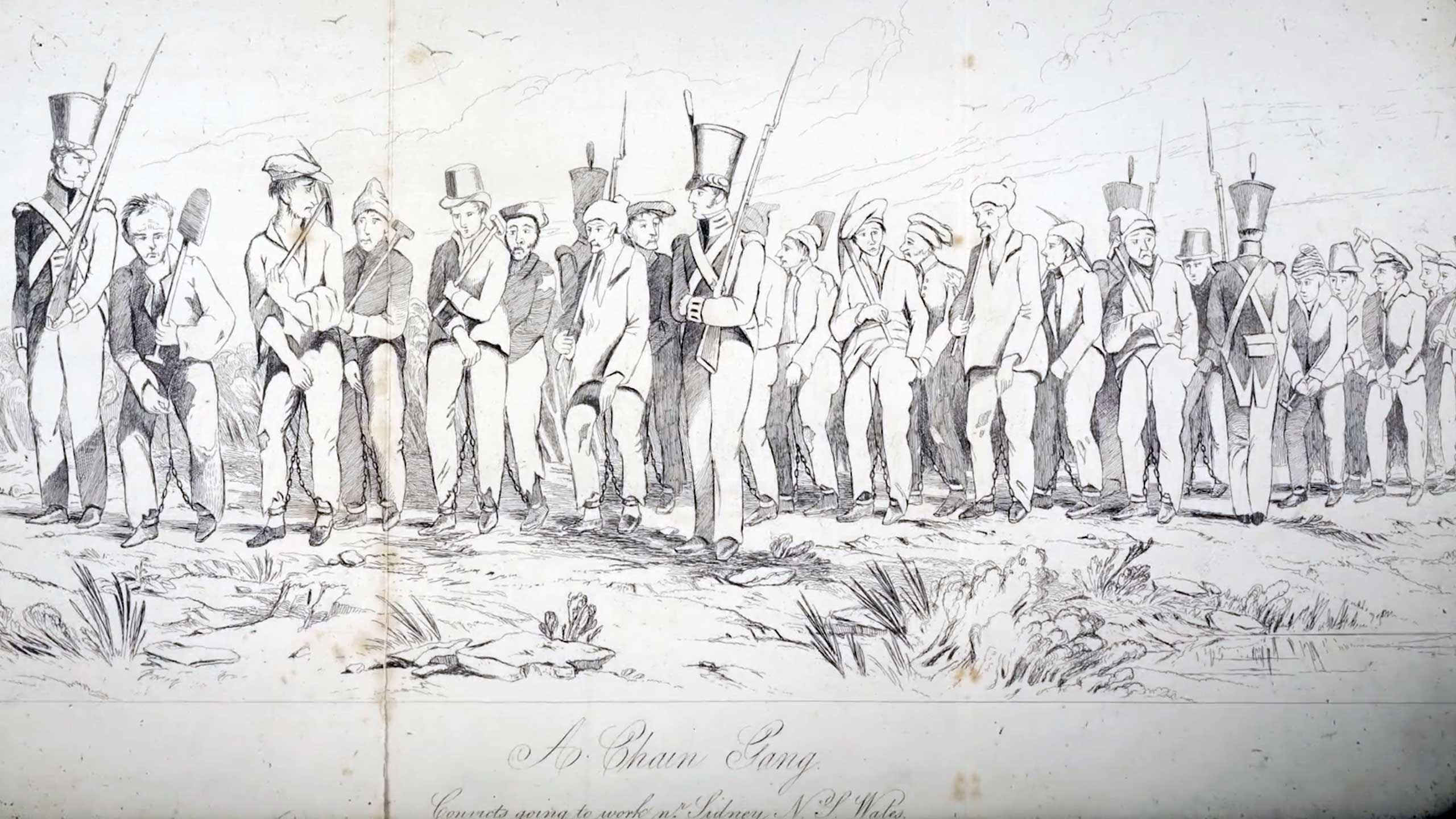

It charts the connections between the 3600 political prisoners transported between 1788 and1868, and the 164,000 ordinary convicts, many of whom were dispossessed in Britain and Ireland by turbo-charged capitalism in traditional craft and agricultural occupations.

It also links them with Indigenous Australians resisting colonialism and exploitation, some of whom found themselves in the convict system and exiled from Country.

Conviction Politics isn’t yet complete, but as it stands it’s a huge history realisation essentially about one thing. How did these highly politicised groups, fighting for basic workers’ rights and human rights, carry on with this activism once sent “out of sight” to Tasmania or New South Wales?

Who were they, what did they do, and what did all mean for post-colonial, democratic Australia?

The hub was launched by Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) secretary Sally McManus on the Monash Caulfield Campus yesterday.

In this extract below of one of the new hub’s mini-documentaries, titled First Impressions, Associate Professor Moore explains why these politically-charged activists found themselves in Australia, and why the British plan to ship them thousands of miles away to an isolated colony in order to silence them spectacularly backfired.

First Impressions

First Impressions

“Collective” is the key word. A fledgling unionism. “I’m interested in marginal groups that assert themselves and have an impact on mainstream cultural politics.”

Associate Professor Moore also explains the situation of a large group of Irish political convicts sent to Sydney, where they were effectively prisoners, but worked on government farms and for government leaders rather than being jailed.

“They were part of a machine akin in a way to slavery,” he says, confronted once again, in Australia, the colonial powers the British had already enacted in Ireland. Except here, no one spoke Gaelic (apart from themselves), and they had fewer rights than they did in Ireland.

Conviction Politics collaborator Professor Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, of the University of New England in New South Wales, outlines the scene for political convicts who were taken to Hobart rather than Sydney: “The streets of Hobart had many accents from across the British Empire – accents from the Caribbean, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the Midlands, London. It was a veritable Tower of Babel.”

He says that after arriving up the Derwent River, the men were sent to jail and the women to a “facility” called the Cascades Female Factory. There were 13 of these across Tasmania and New South Wales in the 1800s, in which women lived and worked – sewing, plaiting, weaving, laundry. Many of these became quickly “organised”.

One curious but highly symbolic event at the Cascades Female Factory is documented with dramatisation and animation in the mini-doc We Are All Alike.

No spoilers, but if you watch the extract below, you’ll see the Irish women enslaved in the factory in a swampy part of Hobart had simply had enough. Any respect they may had for their captors had vanished, and they became both contemptuous of them – but also very proud of their collective identity.

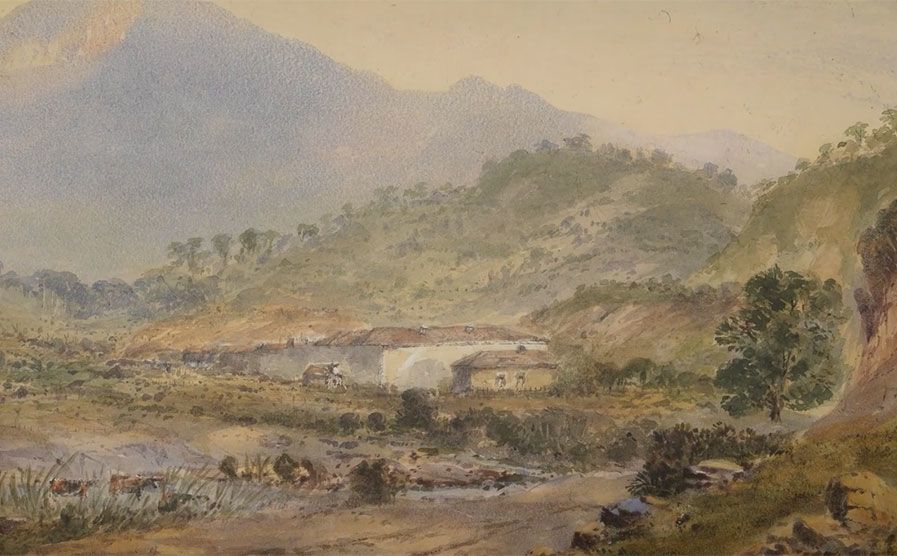

Cascades Female Factory, Hobart Tasmania. (Picture supplied: Crowther Library, State Library of Tasmania)

Cascades Female Factory, Hobart Tasmania. (Picture supplied: Crowther Library, State Library of Tasmania)

“Collective” is the key word. A fledgling unionism. “I’m interested in marginal groups that assert themselves and have an impact on mainstream cultural politics,” says Associate Professor Moore. “I’m also interested in histories that span not just one period, but go through many decades or many generations to have an impact today.”

He cites the late Welsh cultural historian Raymond Williams:

“He said that drawing a new line with the past, and making connections that have never been seen before, can be a radical contemporary change.

In the 1800s the convict women were sent to a “facility” called the Cascades Female Factory, in a swampy part of Hobart.

In the 1800s the convict women were sent to a “facility” called the Cascades Female Factory, in a swampy part of Hobart.

In the 1800s, the convict women were sent to a “facility” called the Cascades Female Factory, in a swampy part of Hobart.

In the 1800s, the convict women were sent to a “facility” called the Cascades Female Factory, in a swampy part of Hobart.

In the 1800s the convict women were sent to a “facility” called the Cascades Female Factory, in a swampy part of Hobart.

In the 1800s the convict women were sent to a “facility” called the Cascades Female Factory, in a swampy part of Hobart.

One highly symbolic event at the Cascades Female Factory is documented in the mini-documentary We Are All Alike.

One highly symbolic event at the Cascades Female Factory is documented in the mini-documentary We Are All Alike.

One highly symbolic event at the Cascades Female Factory is documented in the mini-documentary We Are All Alike.

One highly symbolic event at the Cascades Female Factory is documented in the mini-documentary We Are All Alike.

One highly symbolic event at the Cascades Female Factory is documented in the mini-documentary We Are All Alike.

One highly symbolic event at the Cascades Female Factory is documented in the mini-documentary We Are All Alike.

The Irish women enslaved in the factory became contemptuous of their captors, but also proud of their collective identity.

The Irish women enslaved in the factory became contemptuous of their captors, but also proud of their collective identity.

The Irish women enslaved in the factory became contemptuous of their captors, but also proud of their collective identity.

The Irish women enslaved in the factory became contemptuous of their captors, but also proud of their collective identity.

The Irish women enslaved in the factory became contemptuous of their captors, but also proud of their collective identity.

The Irish women enslaved in the factory became contemptuous of their captors, but also proud of their collective identity.

The Irish women enslaved in the factory became contemptuous of their captors, but also proud of their collective identity.

The Irish women enslaved in the factory became contemptuous of their captors, but also proud of their collective identity.

“I have a theory that the colonies tend to forget their own history. White Australia hasn’t been good at telling its own story, and hasn’t been good at remembering it. When you look at political convict behaviour such as absconding and collectivism and strikes, suddenly you realise large groups were doing it. It’s collective resistance.

“We’ve always talked about the 1890s as this period of massive industrial unrest in Australia, which the Labor Party was born from. They had the poets and the writers at the time, such as Henry Lawson.

“But it turns out the 1830s, with unfree convict work, was in as much tumult. We can see groups forming combinations in the 1820s that we can recognise as unions, bargaining for rights.”

“White Australia hasn’t been good at telling its own story, and hasn’t been good at remembering it.”

What that shows, he says, are that “egalitarianism, democracy and solidarity transported in chains from Britain and Ireland are deep in our DNA”.

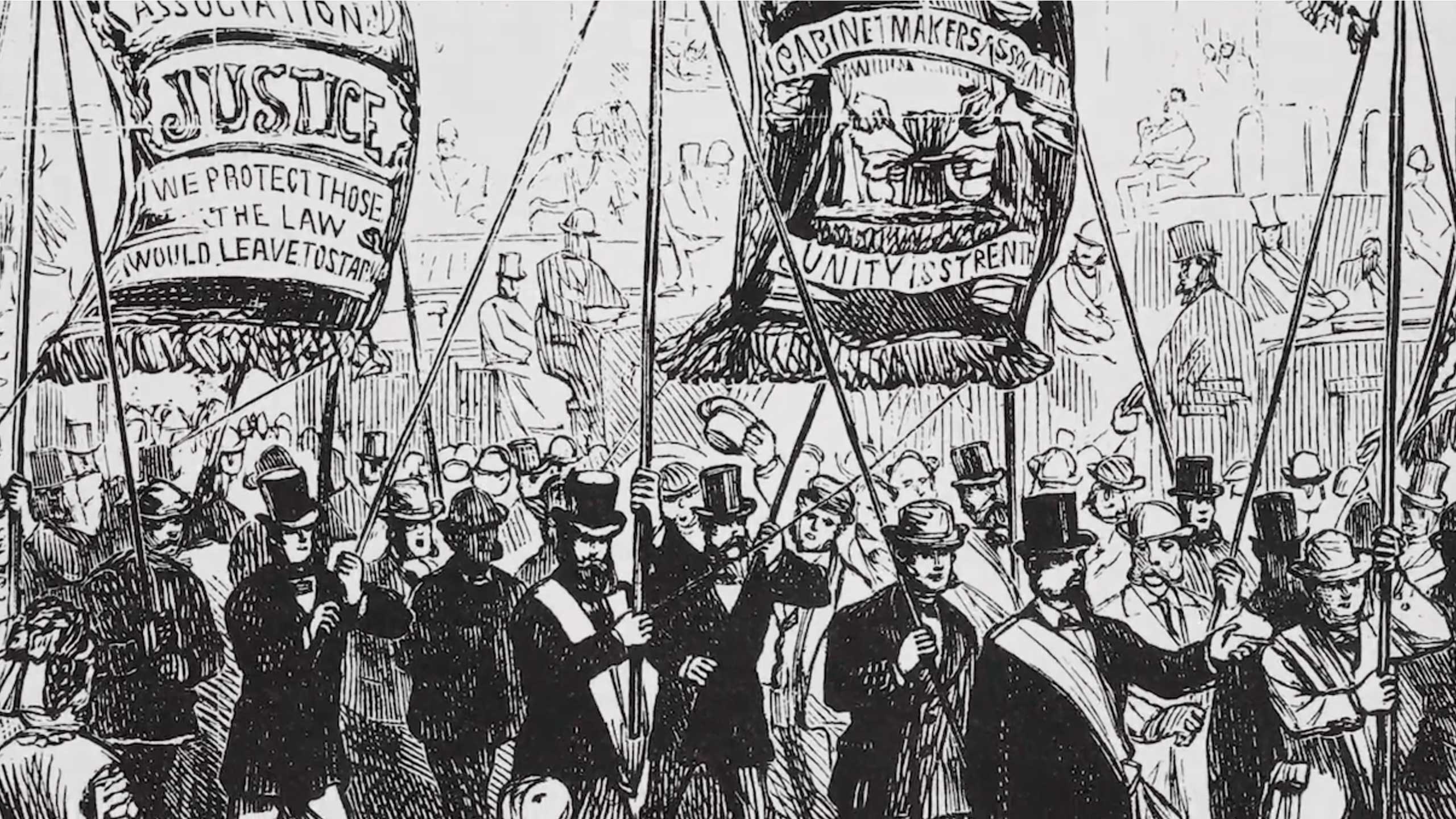

Conviction Politics shows that political convicts and the movements they formed led to ...

Free press, trade freedoms, the anti-transportation movement ...

Better government, more voting rights, the birth of the labour movement ...

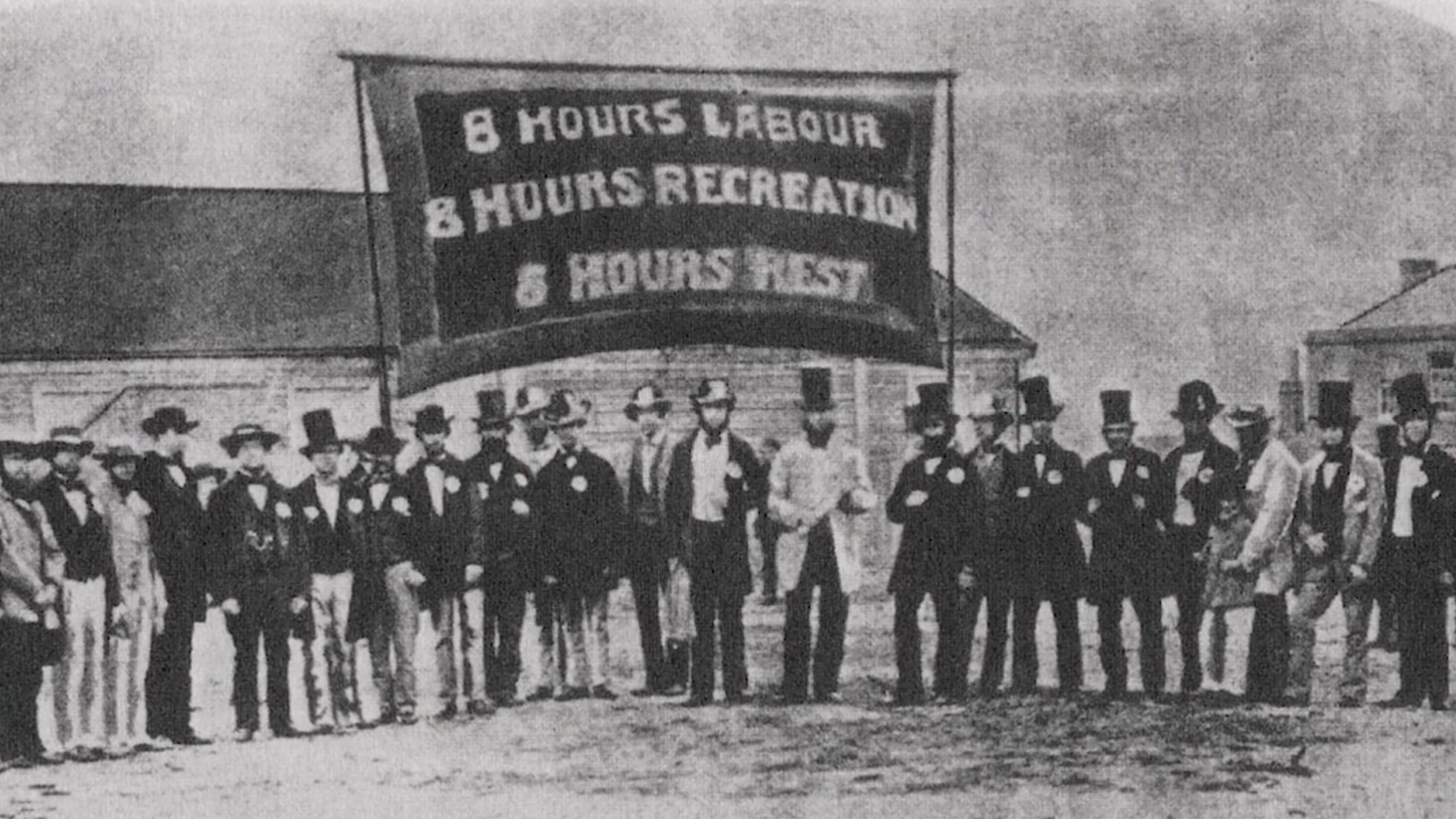

Land distribution, industrial regulation, home ownership, and the eight-hour day.

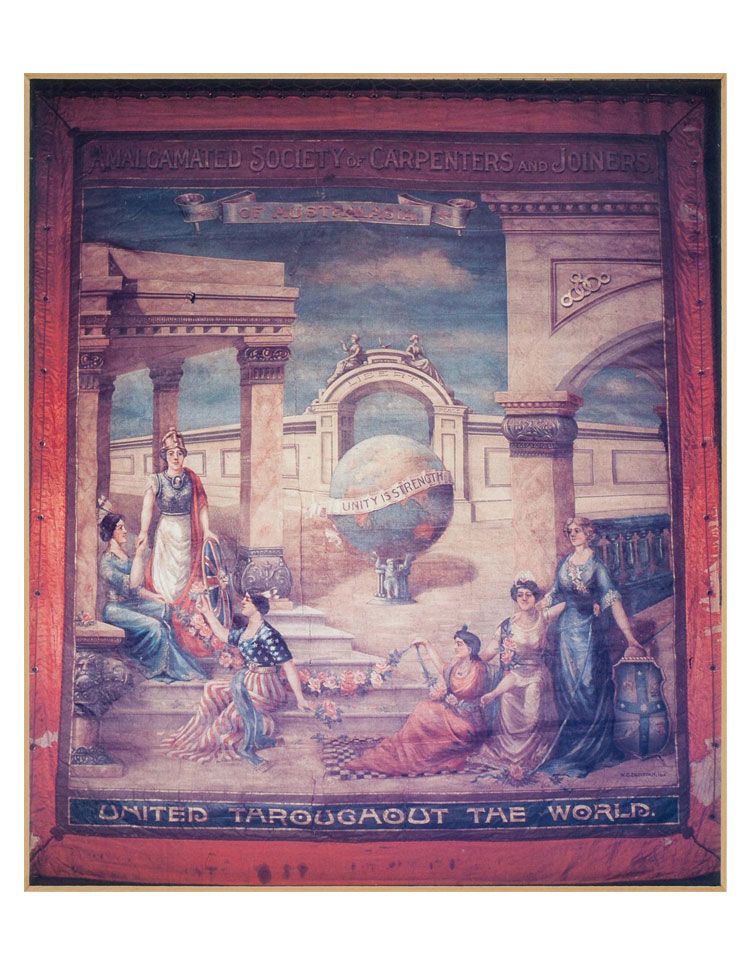

Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners banner, 1914. (Source: Museums Victoria)

Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners banner, 1914. (Source: Museums Victoria)

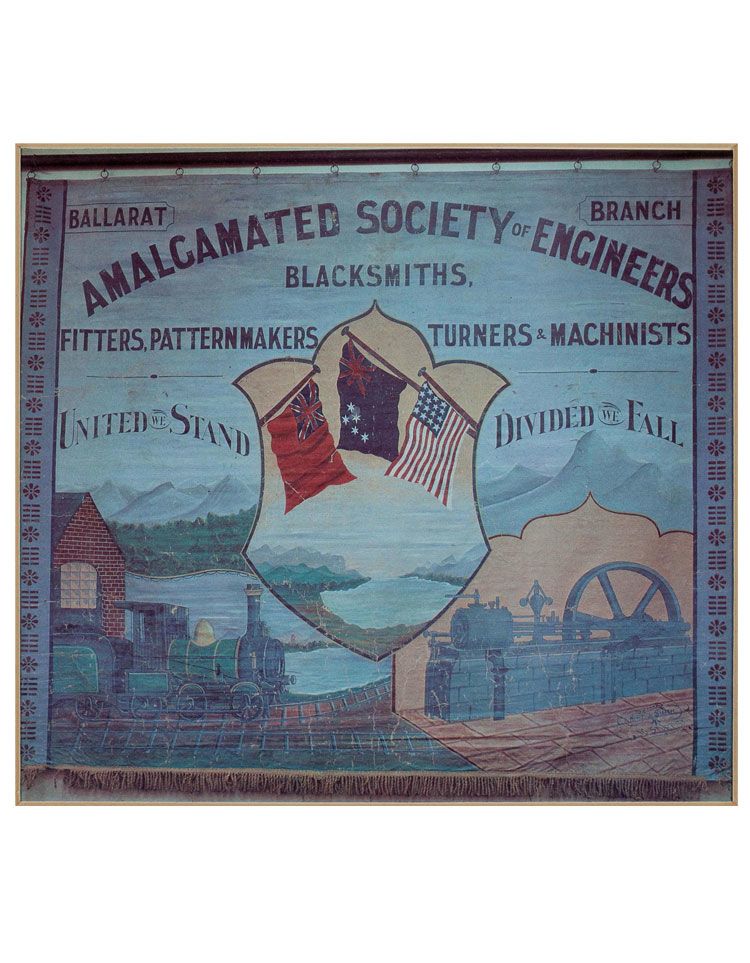

Amalgamated Society of Engineers, Blacksmiths, Fitters, Patternmakers, Turners and Machinists, Ballarat Branch. (Source: Museums Victoria)

Amalgamated Society of Engineers, Blacksmiths, Fitters, Patternmakers, Turners and Machinists, Ballarat Branch. (Source: Museums Victoria)

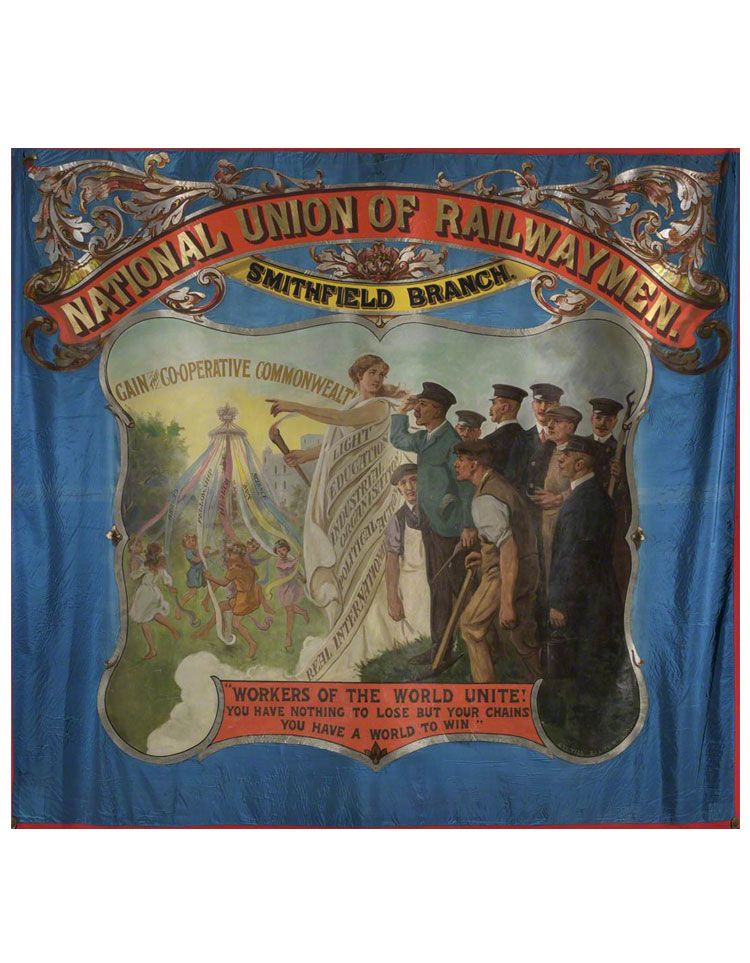

National Union of Railwaymen, Smithfield Branch banner, 1925. (Source: People's History Museum)

National Union of Railwaymen, Smithfield Branch banner, 1925. (Source: People's History Museum)

It was “the British Empire’s Guantanamo Bay”, Associate Professor Moore told the ABC, yet they helped turn an unfree and unequal outpost into a democracy.

The new mapping shows that political convicts were a diverse group united by common goals. They were radical democrats, Irish republicans (Fenians), Luddites (radicalised British textile workers), Swing Rioters and Tolpuddle Martyrs (disenfranchised British farm workers), and Chartists (working-class activists).

They all had their own mediums and artforms, leading to an archive of songs, stories, cartoons, banners, poetry, badges, posters and novels.

Many also sported unusual tattoos.

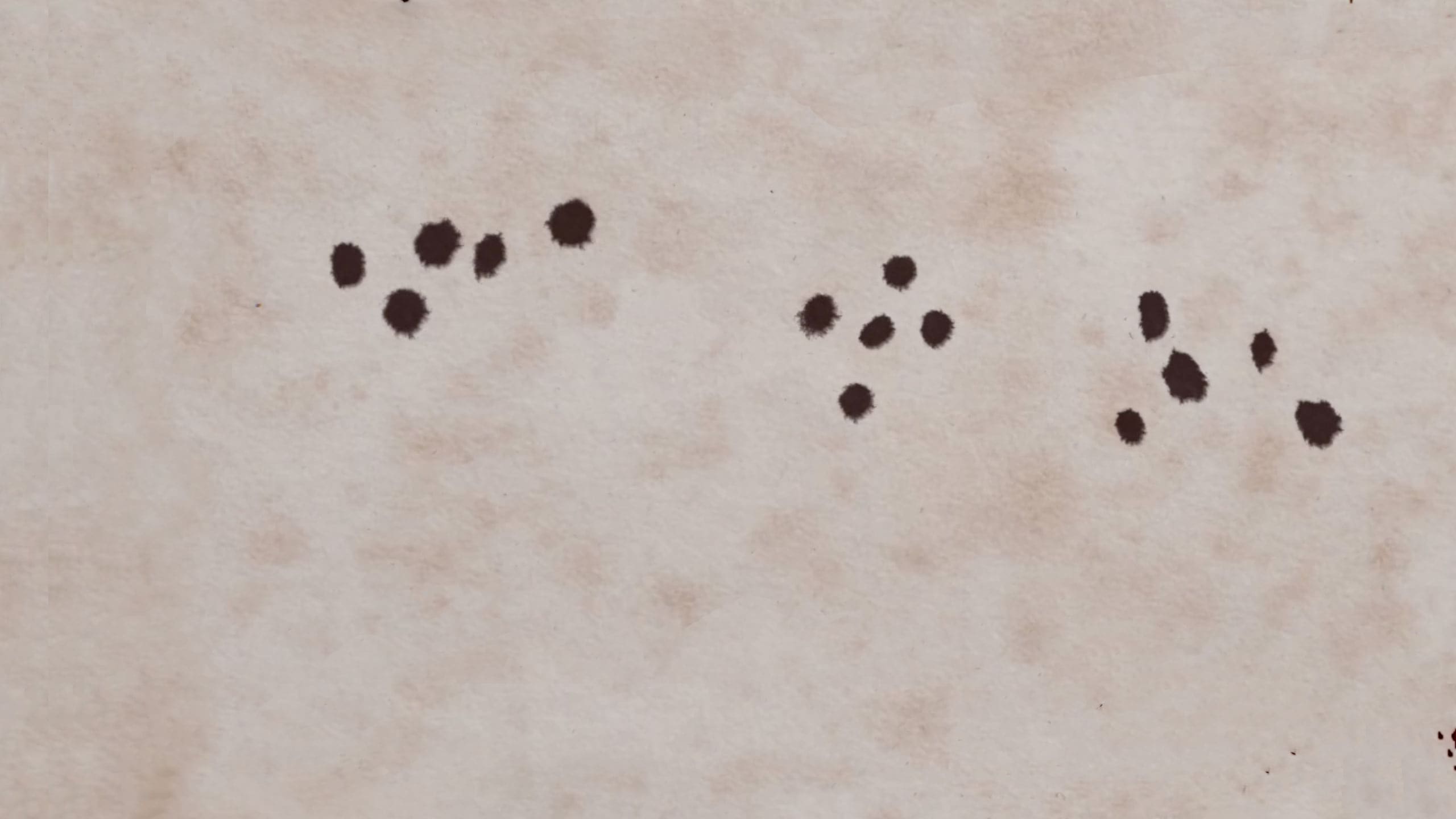

A large number of convicts arrived in Australia sporting tattoos – about one in five men, and one in five women.

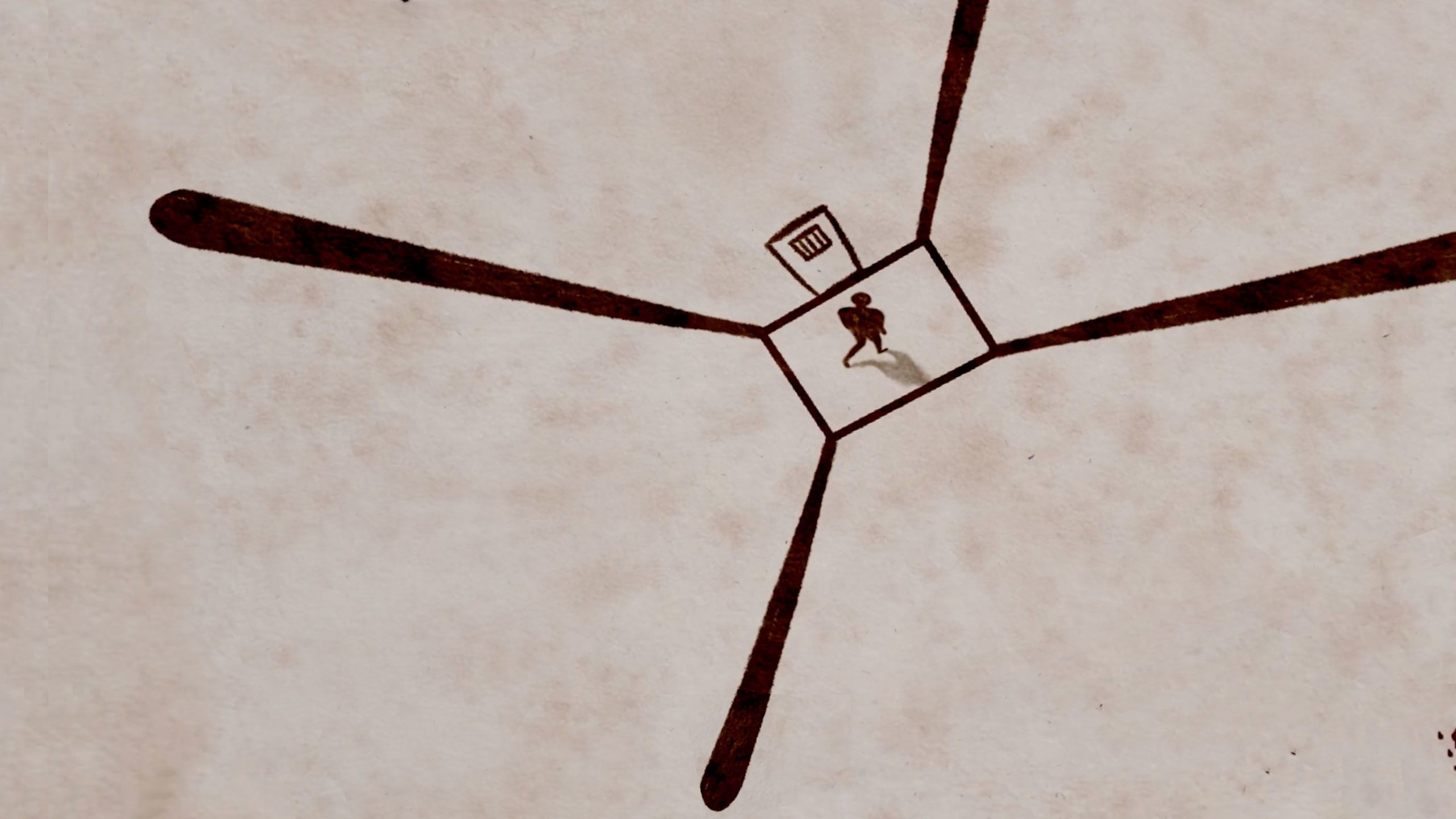

Many juvenile convicts arrived in Van Diemen’s Land and NSW with dots on their bodies.

Most commonly, they were in group patterns of five or seven dots.

In particular, five dots between the thumb and forefinger on the left hand.

It’s believed the tattoos showed the convicts had spent time in prison before coming to Australia – the central dot signified the prisoner, and the others the corners of the cell.

“Australia is where Chartism succeeds.”

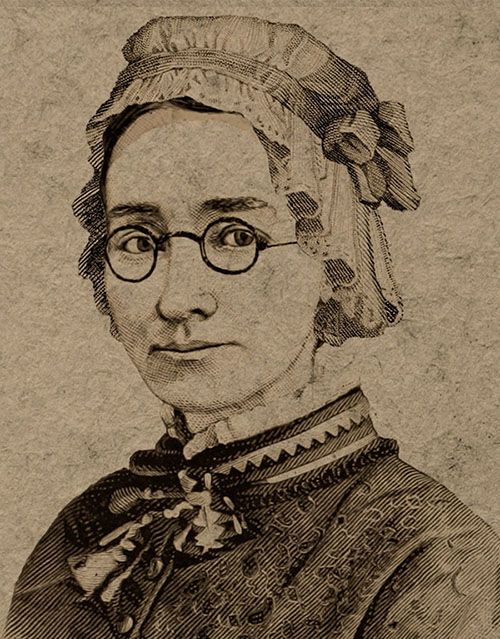

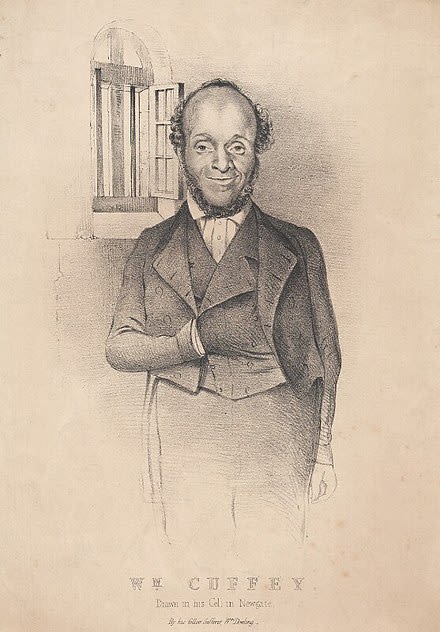

Central to the Conviction Politics narrative is an extraordinary character named William Cuffay, a black man from the south of England who was the son of a freed slave from the West Indies, and the grandson of a man kidnapped from Africa and sent into slavery. Cuffay, a tailor, was a leader of the Chartists in Britain.

The Chartists’ charter – or list of demands – was as follows:

- All men get the vote (universal manhood suffrage).

- Voting by secret ballot.

- Parliamentary elections every year.

- Constituencies of equal size.

- Members of parliament should be paid.

- The property qualification for becoming a member of parliament should be abolished.

In 1839, the Chartists’ demands were presented to the House of Commons with more than 1.25 million signatures. It was rejected, which provoked unrest that was swiftly crushed by the authorities. A second petition was presented in 1842, signed this time by more than three million people, but again it was rejected, and further unrest and arrests followed.

Cuffay was arrested and sent to Tasmania in 1849, and became a leader of the nascent Australian labour movement.

“Australia is where Chartism succeeds,” says Dr Moore. “Cuffay became a union leader almost as soon as he got off the boat, and his big cause became the Masters and Servants Act, which decreed that servants must be loyal to their employers, and imposed jail with hard labour for infringements, effectively preventing collective action or unionism.

“We became known as a ‘Chartists’ democracy,” Associate Professor Moore says.

By the 1860s the six points in the charter has been realised in Victoria and New South Wales.

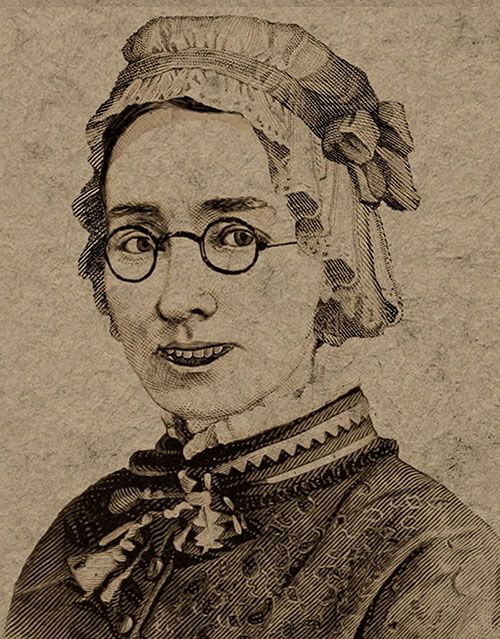

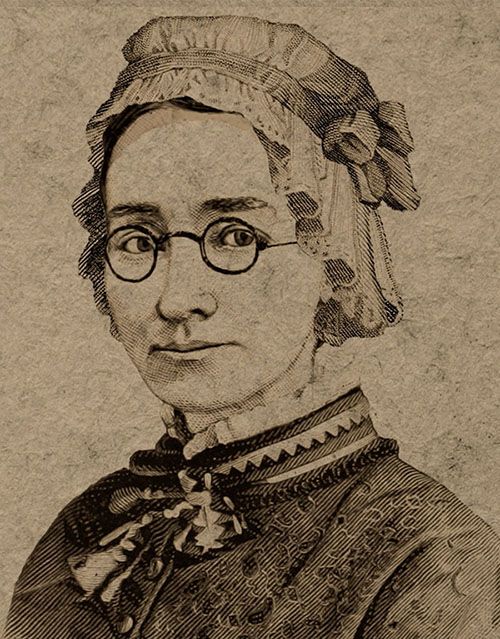

William Cuffay was a leading figure in the Chartists’ movement of 1836-1848.

William Cuffay was a leading figure in the Chartists’ movement of 1836-1848.

The Hub and its media content were created by project partner and digital storytellers Roar Film, an award-winning production house. Conviction Politics is an extension of Associate Professor Moore’s book and documentary series of 2015, Death or Liberty, also produced by Roar, and directed by Steve Thomas, partner investigator on the latest project.

We acknowledge and pay respects to the Elders and Traditional Owners of the land on which our four Australian campuses stand. Information for Indigenous Australians

Registered Higher Education Provider, TEQSA Act 2011, ABN 12 377 614 012

CRICOS provider number, Monash University: 00008C