‘I’ve never met anyone who has found so much strength’

Verdant Gadhavi

Verdant Gadhavi

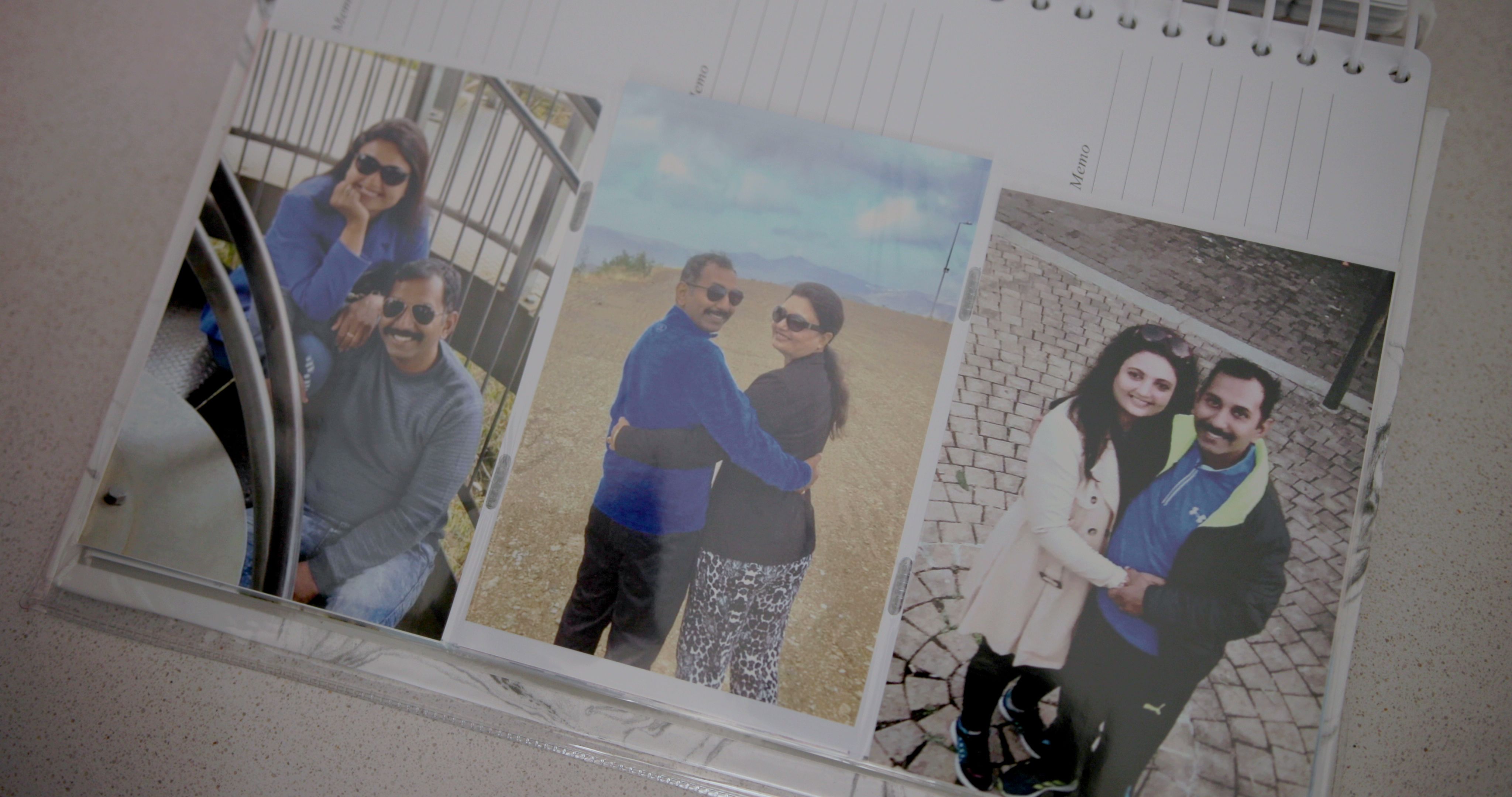

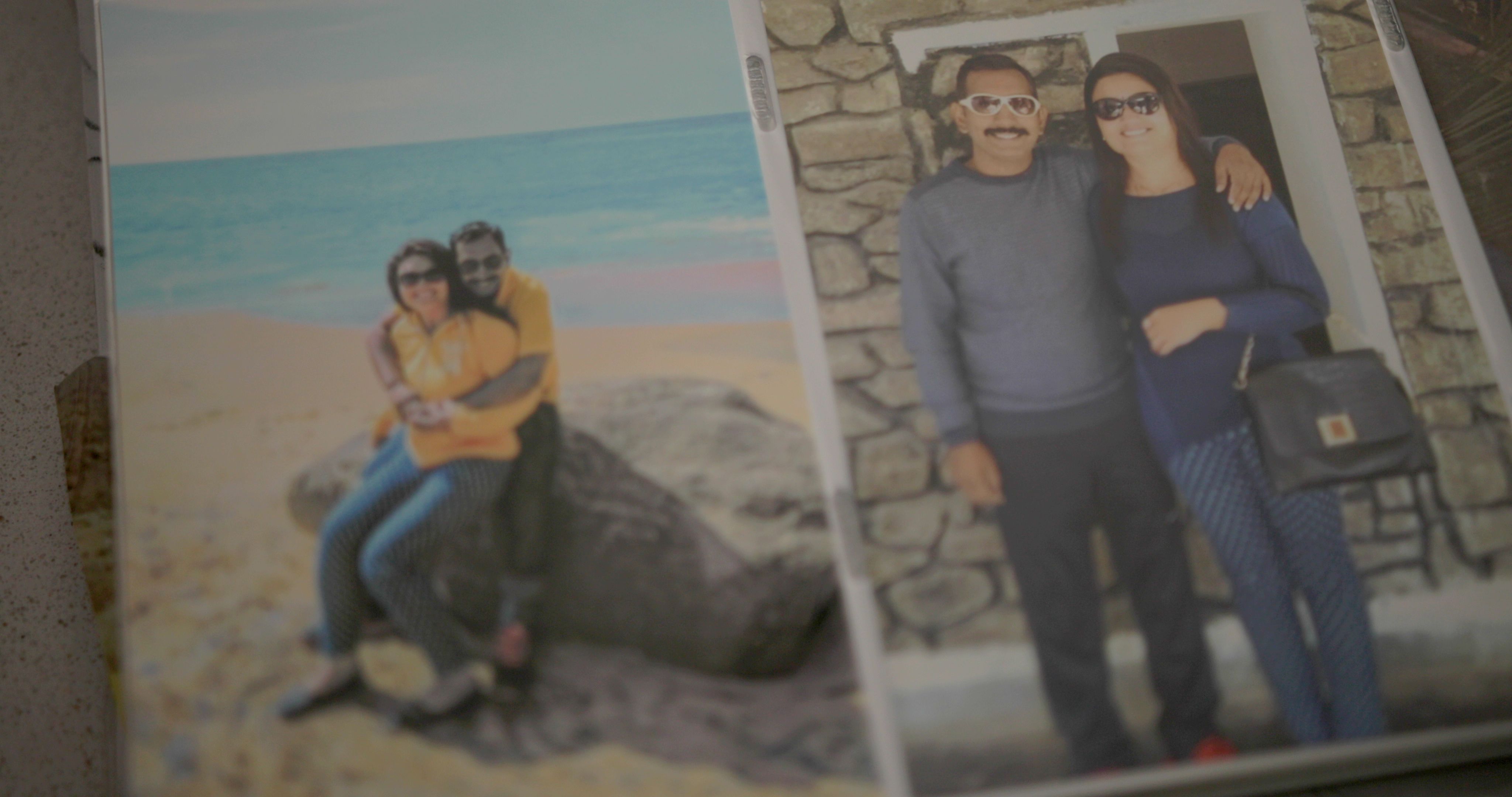

Vedant has certain things he keeps, the treasures and memories and the feelings of what used to be.

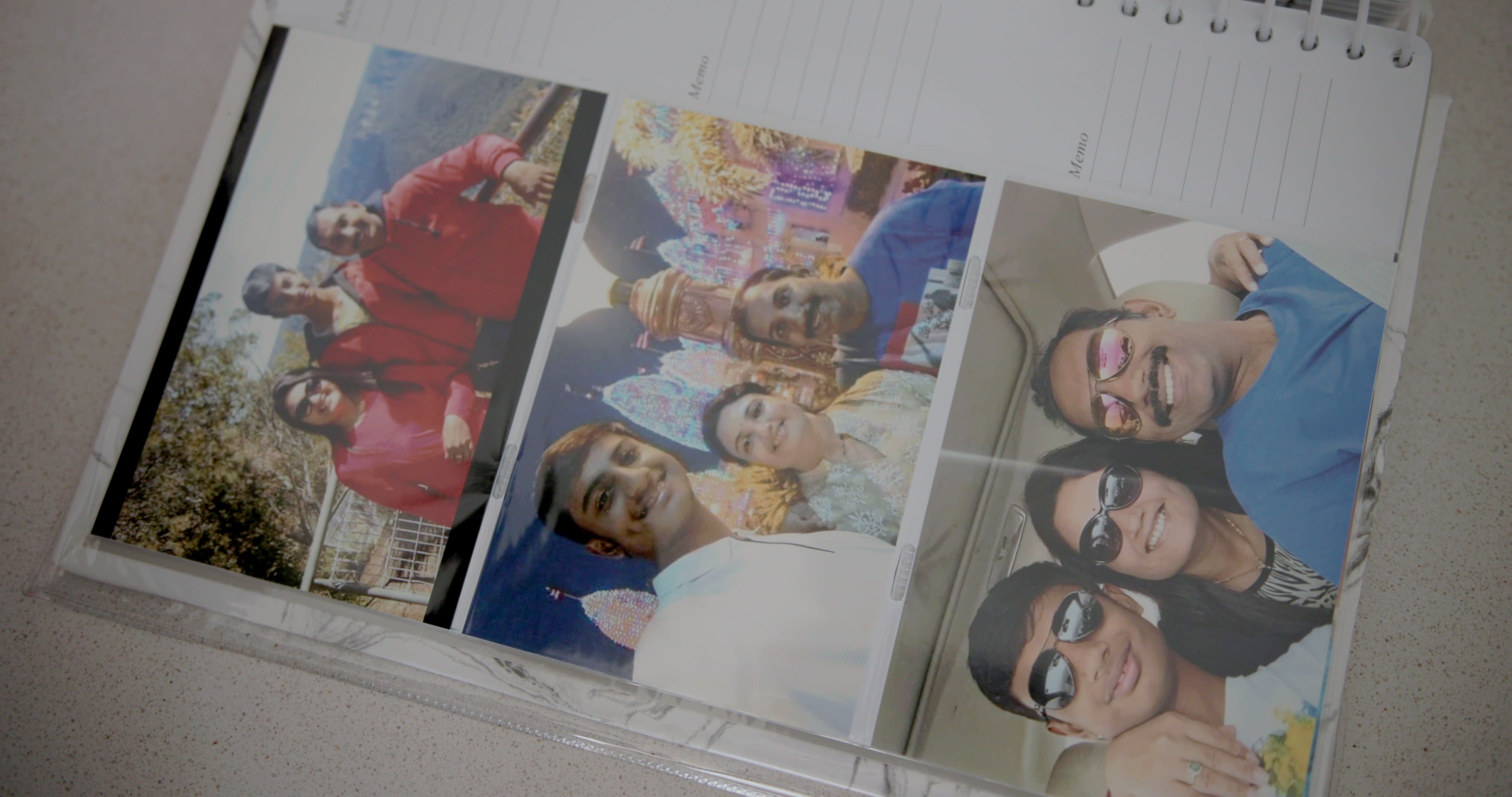

He wears a gold ring from his mother. He has photographs laminated and hung, voice messages on his phone from his father, he has jewellery, all gold, still bright.

He keeps items of clothing in a white box under his bed; brilliant saris of his mothers, his father’s work uniforms with the company badge.

“Also some of Mum’s T-shirts,” he says, “the clothes I used to see her wearing. I can still see them and feel them, clothes my mother looked pretty in. My father’s uniforms, because he served his company.”

These things are his memories, but they’re also signals of how best to move forward, who to be, how to proceed.

The ‘miracle’

Monash student Vedant Gadhavi – an only child – was in the car, but carried out alive. He calls this his “miracle”.

He had just turned 18 and was wearing the gold birthday ring, asleep in the back seat of the car, with Mum in the front, Dad driving, in Saudi Arabia where his father worked.

In his room now in Tarneit, in Melbourne’s western suburbs, safe in the bosom of his Indian uncle and aunt, he sometimes kisses the laminated photographs of his lost parents, asking them for help, asking them for strength or thanking them for good tidings.

He’s written on them – “Always in my Heart”, “Fly High until we Meet Again”, and “Sometimes I Look at You and Wonder How I Got To Be So Damn Lucky”.

He’s not lost in grief, as he has every right to be. In the six months I’ve known Vedant, I’ve never seen him anything other than positive. He’s thankful for them and their gifts, and he’s thankful for surviving. He knows he needs to push on and excel as best he can in their memories.

“There are times when maybe I’m stressed out or an exam goes bad, then I can talk to Mum or Dad in the photos and ask them for help taking care of this thing,” he says, softly.

“I was closest to them, so whatever I say, they’ll hear. I feel their presence. I talk to them. If something good happens, too, I talk. Honestly, good things are happening.”

WATCH: Vedant Gadhavi, Monash student shares his story.

WATCH: Vedant Gadhavi, Monash student shares his story.

The crash that changed the young biomedicine student’s life was in hilly country on a rough road just 38 minutes from their destination of Jeddah, where his father was a petrochemical engineer. It had been a long, long drive from the city of Riyadh, where Vedant and his mother had been COVID-quarantining.

Vedant was in the front with his dad until 9pm. He has videos on his phone of those hours; he put the phone on the dash and filmed them joking, teasing, laughing and singing along riotously to Bollywood songs.

They’re eerie to watch now, but they show the joy and fun Vedant says his parents both exuded.

About 9pm, his mother saw Vedant was getting tired and said he should lie down in the back with a neck pillow; she moved to the front. He stretched his legs out. No seatbelt.

He remembers drifting in and out of sleep just before it happened, hearing his mother reminding his father to be careful. They collided with a truck on a shortcut off the freeway the locals called “Death Road”.

The crash was mad noise, then silence. We know they were exactly 38 minutes from home, because Vedant’s father’s phone was recovered from the wreckage, and on it was the map they were following, frozen in time.

Vedant was taken in an ambulance to a small nearby hospital, then on to a large private one belonging to the petrochemical company his father worked for.

Everything changed in a flash of light. As his parents died in their front seats, Vedant Gadhavi was unconscious and seriously injured in what was left of the back, one leg all mangled, his face torn and broken, bleeding heavily, his breathing perilously flat.

But he was alive. Probably it was for the best that everything went black for him at that moment on the road with the truck.

There are some things a good son shouldn’t see.

The crash that changed the young biomedicine student’s life was in hilly country on a rough road just 38 minutes from their destination of Jeddah, where his father was a petrochemical engineer. It had been a long, long drive from the city of Riyadh, where Vedant and his mother had been COVID-quarantining.

Vedant was in the front with his dad until 9pm. He has videos on his phone of those hours; he put the phone on the dash and filmed them joking, teasing, laughing and singing along riotously to Bollywood songs.

They’re eerie to watch now, but they show the joy and fun Vedant says his parents both exuded.

About 9pm, his mother saw Vedant was getting tired and said he should lie down in the back with a neck pillow; she moved to the front. He stretched his legs out. No seatbelt.

He remembers drifting in and out of sleep just before it happened, hearing his mother reminding his father to be careful. They collided with a truck on a shortcut off the freeway the locals called “Death Road”.

The crash was mad noise, then silence. We know they were exactly 38 minutes from home, because Vedant’s father’s phone was recovered from the wreckage, and on it was the map they were following, frozen in time.

Vedant was taken in an ambulance to a small nearby hospital, then on to a large private one belonging to the petrochemical company his father worked for.

Everything changed in a flash of light. As his parents died in their front seats, Vedant Gadhavi was unconscious and seriously injured in what was left of the back, one leg all mangled, his face torn and broken, bleeding heavily, his breathing perilously flat.

But he was alive. Probably it was for the best that everything went black for him at that moment on the road with the truck.

There are some things a good son shouldn’t see.

A close-knit Hindu family

His mother’s name was Mamta, his father Piyush. Both were just 44 when they died.

Mamta was a teacher, but became what we could call a “homemaker” with Vedant while her husband was away – either elsewhere in India or the Middle East – working as a petrochemical engineer with polypropylene for Reliance Industries, an Indian multinational. Vedant grew up in the city of Vadodara, in the western state of Gujarat.

“My mum used to teach,” Vedant says, “but once I was born, just for me, she quit. She stayed with me, and my grandparents, just for me, just to take care of me. I would say she dedicated the whole of her life to me.”

His father moved to Saudi Arabia when Vedant was 12, but there were regular visits both ways.

“I feel like he chose to be alone in another country for my betterment. He worked hard to get good opportunities to help me … He was the happiest person, very chill, very fun. He was a big fan of cricket, the gym, the stock market, he would take us out on drives. A very outgoing, very nice guy.”

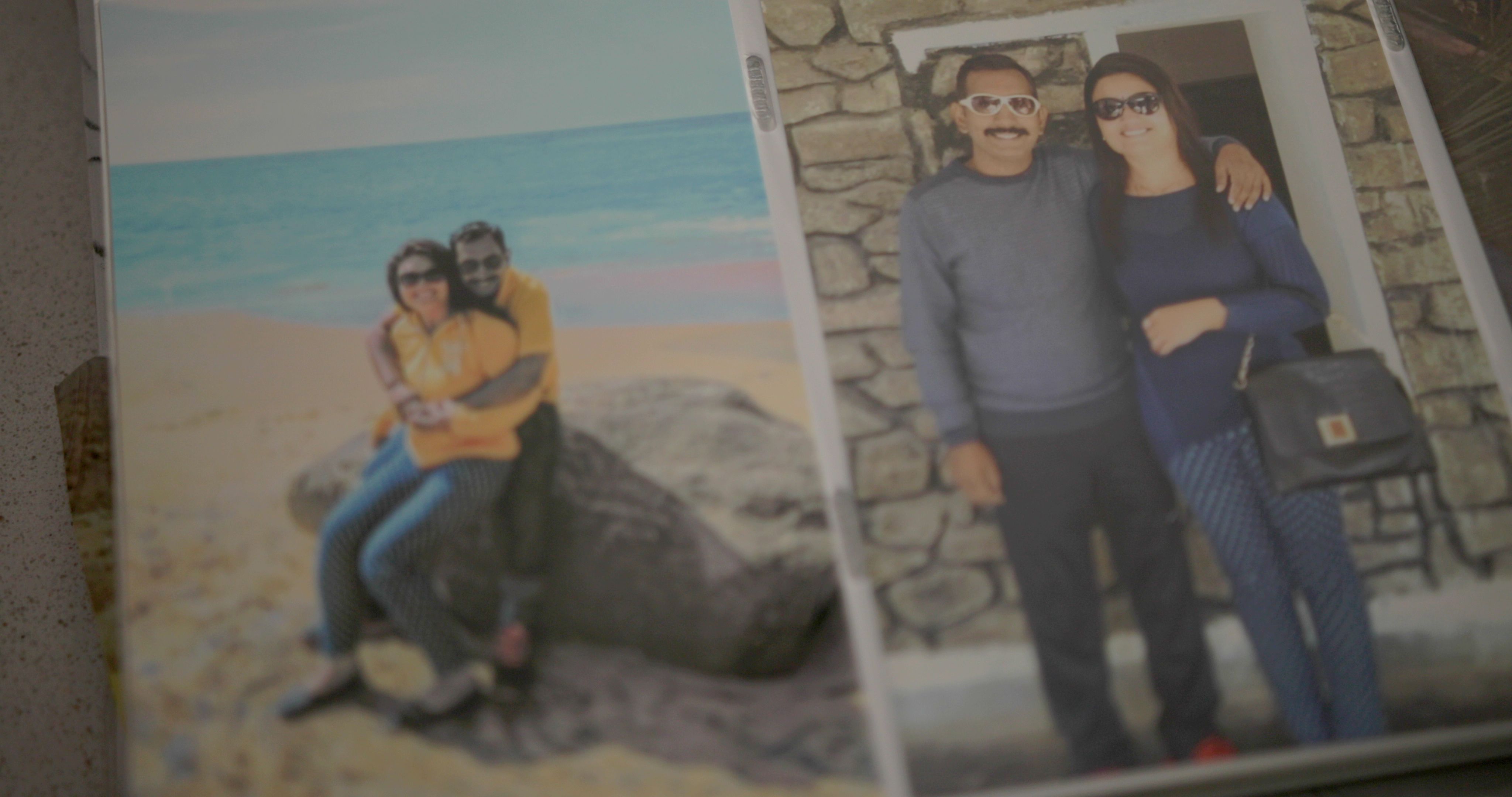

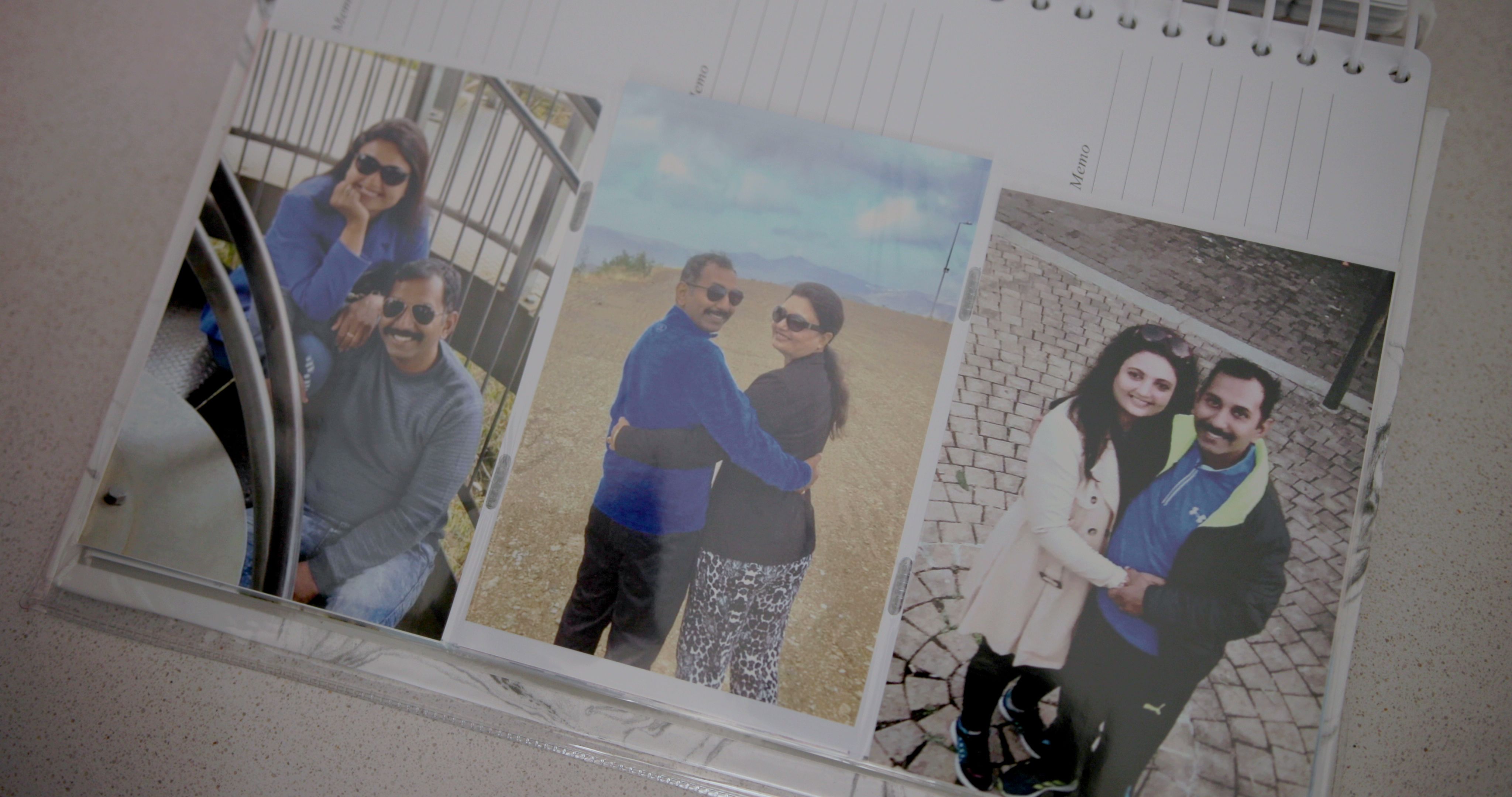

Despite the physical distance between them for so long, they were a close Hindu family, the kind of family that wore matching colours for outings, and they photographed more or less everything they did.

A close-knit Hindu family

His mother’s name was Mamta, his father Piyush. Both were just 44 when they died.

Mamta was a teacher, but became what we could call a “homemaker” with Vedant while her husband was away – either elsewhere in India or the Middle East – working as a petrochemical engineer with polypropylene for Reliance Industries, an Indian multinational. Vedant grew up in the city of Vadodara, in the western state of Gujarat.

“My mum used to teach,” Vedant says, “but once I was born, just for me, she quit. She stayed with me, and my grandparents, just for me, just to take care of me. I would say she dedicated the whole of her life to me.”

His father moved to Saudi Arabia when Vedant was 12, but there were regular visits both ways.

“I feel like he chose to be alone in another country for my betterment. He worked hard to get good opportunities to help me … He was the happiest person, very chill, very fun. He was a big fan of cricket, the gym, the stock market, he would take us out on drives. A very outgoing, very nice guy.”

Despite the physical distance between them for so long, they were a close Hindu family, the kind of family that wore matching colours for outings, and they photographed more or less everything they did.

He remembers drifting in and out of sleep just before it happened, hearing his mother reminding his father to be careful.

Vedant and his girlfriend, Ayushi.

Vedant and his girlfriend, Ayushi.

Ayushi Patel

Ayushi Patel

Vedant was always a good student. He went to the same school through primary and secondary because he liked it. He’s sporty; he played football for India as a schoolboy. He also won prizes for chess, and represented India in a spelling bee – for his school – in Dubai.

His girlfriend, Ayushi Patel, (pictured at the football with Verdant) is also from Gujarat, from a city called Gandhinagar, three hours from Vadadora. They met when they were both nine years old because their fathers both worked for the same company in Saudi Arabia. They met at a company party and became friends, then started dating two years ago.

She called Piyush and Mamta “aunt” and “uncle” because they all spent so much time together In Saudi Arabia at their fathers’ workplace compound.

“We lived next door, so from morning tea until late at night we would be together, we would have our food together, we would play together,” she says. “Most of our time we spent together.”

At first, Ayushi didn’t like Vedant, because everyone adored him and she was jealous.

“I thought I should be loved!” she says. “Not him! I used to be the most-loved kid there, everyone gave me attention. All of a sudden he came into the game!”

But they became great buddies, and Ayushi became very close to Vedant’s parents.

“They were both very sweet,” she says. “His dad was one of the sweetest people; my dad really liked his dad a lot, and I did, too.

“His mum was super-sweet; he was a mummy’s boy. She was always very particular about his schedule, looking after him, his breakfast, his snacks, drinks, his school uniforms, then football training. She lived for him, she raised him a certain way, in a very good way.”

Ayushi is in Melbourne now, too. She wasn’t going to be. She was accepted into a university in California, in Silicon Valley, to study computer science. This was as Vedant was first enrolling at Monash University, their relationship only just blossoming. They were to go their separate ways and maybe try a very-long-distance relationship after being friends for a decade.

“I had started finding him very attractive,” she says. “His mindset, the way he talks, the way he expresses himself. He’s very grounded, very humble and very modest. I love his personality, the way he does everything and all. He’s a great guy.”

Ayushi was at home in India when the crash happened, preparing to go to California. Vedant was soon to come on his own to Melbourne and Monash. They were chatting and messaging all the time.

One morning, Indian time, his usual text didn’t come … and still didn’t come.

He wasn’t replying, either. A little strange, she thought. Out of character.

Vedant was always a good student. He went to the same school through primary and secondary because he liked it. He’s sporty; he played football for India as a schoolboy. He also won prizes for chess, and represented India in a spelling bee – for his school – in Dubai.

His girlfriend, Ayushi Patel, (pictured at the football with Verdant) is also from Gujarat, from a city called Gandhinagar, three hours from Vadadora. They met when they were both nine years old because their fathers both worked for the same company in Saudi Arabia. They met at a company party and became friends, then started dating two years ago.

Vedant and his girlfriend, Ayushi Patel.

Vedant and his girlfriend, Ayushi Patel.

She called Piyush and Mamta “aunt” and “uncle” because they all spent so much time together In Saudi Arabia at their fathers’ workplace compound.

“We lived next door, so from morning tea until late at night we would be together, we would have our food together, we would play together,” she says. “Most of our time we spent together.”

At first, Ayushi didn’t like Vedant, because everyone adored him and she was jealous.

“I thought I should be loved!” she says. “Not him! I used to be the most-loved kid there, everyone gave me attention. All of a sudden he came into the game!”

But they became great buddies, and Ayushi became very close to Vedant’s parents.

“They were both very sweet,” she says. “His dad was one of the sweetest people; my dad really liked his dad a lot, and I did, too.

“His mum was super-sweet; he was a mummy’s boy. She was always very particular about his schedule, looking after him, his breakfast, his snacks, drinks, his school uniforms, then football training. She lived for him, she raised him a certain way, in a very good way.”

Ayushi is in Melbourne now, too. She wasn’t going to be. She was accepted into a university in California, in Silicon Valley, to study computer science. This was as Vedant was first enrolling at Monash University, their relationship only just blossoming. They were to go their separate ways and maybe try a very-long-distance relationship after being friends for a decade.

Ayushi Patel

Ayushi Patel

“I had started finding him very attractive,” she says. “His mindset, the way he talks, the way he expresses himself. He’s very grounded, very humble and very modest. I love his personality, the way he does everything and all. He’s a great guy.”

Ayushi was at home in India when the crash happened, preparing to go to California. Vedant was soon to come on his own to Melbourne and Monash. They were chatting and messaging all the time.

One morning, Indian time, his usual text didn’t come … and still didn’t come.

He wasn’t replying, either. A little strange, she thought. Out of character.

A fateful phone call

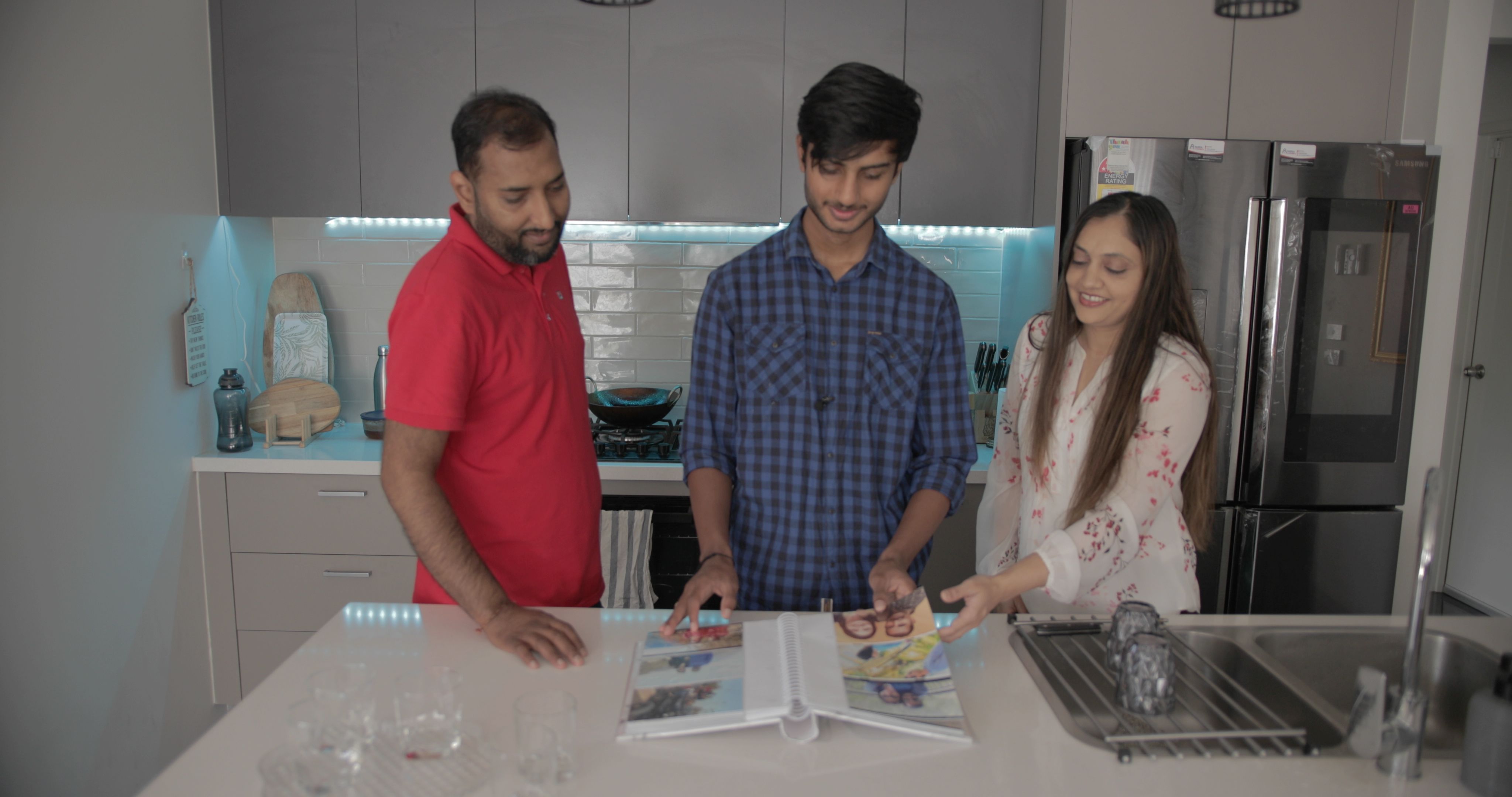

In Tarneit, in Melbourne’s west, Vedant’s uncle and aunt, Anant and Uma Gadhavi, were just sitting down to dinner. Anant is Piyushi’s little brother, and the family resemblance between them and Vedant is striking.

They settled in Melbourne several years ago after a stint working in Adelaide. Their Hindu shrine – in a spare bedroom – is attended to three times a day, and glows with the most colourful of fairy lights.

It was Uma’s birthday. They’d literally just started to eat when Anant’s phone rang.

In Gandhinagar, India, Ayushi’s phone started up, too.

Friends and former colleagues had heard the news – the car was a petrochemical company car with a logo on the side. Word spread fast. Local media began to report the news.

Suddenly, says Uma Gadhavi, the family were thrown into “the most critical situation we have ever faced in our lives”.

“It was hard to believe they were dead and Vedant was so badly injured so far away. So terrible – we don’t want anyone to go through this.”

Ayushi answered her phone. It was Rushi, a friend of hers and Vedant’s, another Indian petrochemical company kid.

“Ayushi, do you know what’s happened?”

“I do not know.”

“Vedant’s car has met with an accident.”

“I thought he was kidding,” she says. “I didn’t believe him. But he said it was true.

Vedant’s uncle and aunt, Anant and Uma Gadhavi.

Vedant’s uncle and aunt, Anant and Uma Gadhavi.

“I asked him, ‘Are they fine?’, she says, “and he said he didn’t know anything except an accident. I started crying, of course, and then I started calling everyone I knew in Saudi Arabia.”

Ayushi was distraught. She wasn’t finding anything out, and caught between a great hope they were fine and a grave fear they were not.

The time zones were cruel, the distance was cruel, the not-knowing was awful.

Two-and-a-half hours later, Rushi rings back. He tells Ayushi that Vedant is alive but critical in hospital. His mother and father are dead.

“He said they were no more,” remembers Ayushi. “This was very shocking.”

Back in Tarneit, Anant and Uma try their best through the fog of shock and sadness to figure out what to do. It was peak COVID-19 at the time and Australia’s borders were closed, with some strict exemptions.

“I was in such a condition,” says Uma, “that I couldn’t even open my laptop.

To tell, or to protect?

So began a liminal period between protection and truth in Vedant’s extraordinary story, a netherworld that lasted three weeks.

When, exactly, should a seriously injured 18-year-old with no brothers or sisters be told his parents are both dead? Is it OK to lie to him, for a little while, until he’s better-placed to find out? Is it better sometimes to withhold the truth?

He was taken from the accident, and when he came to he had stitches in his head, forehead, face, hands and feet, massive blood loss, and a low heart rate.

Teams of colleagues from the petrochemical company had taken over the arrangements at the hospital, the morgue, and also with administrative tasks such as passports, visas and money.

No one said anything, and Vedant was so tranquilised for the pain that he didn’t quite know where he was, or even who he was. There were problems finding the right blood for him, to replace what he’d lost. But he was breathing …

A week or so later, he was cleared to fly back to India; the bodies of his mother and father were on the way there, too, to Vedadora, back home.

By now Anant and Uma had reapplied for visas and been cleared to travel, despite the pandemic.

Vedant was in a wheelchair, still heavily tranquilised, the company paying for the flights and assigning two of his father’s colleagues to go with him as chaperones and carers.

Once home, family members looked after him, but he was still tranquilised and dopey and sleeping most of the day and night. However, Vedant was beginning to figure out that all was not well. The picture forming in his mind was unclear and incomplete.

Ayushi remembers a video call between them around this time, when he was able to talk again. She had seen him before this, on video calls from the hospital with the company people, seeing his injuries and stitches, and also that his hair and beard had grown.

She couldn’t go to Vadadorra to see him yet, because she was busy with family and life matters there that kept her away. She knew he was alive, but she was also scared of the huge challenges ahead.

“All he did that time was keep asking: ‘Where are they? How are they? What is going on? Why am I in India?’,” she says.

“We had to lie and tell him they were in hospital and that he couldn’t talk to them because they would be upset to see his injuries.

“But he was still on such a high dose of medicine that he didn’t know what was happening – he forgets everything and sleeps, for his recovery.”

But the moment must arrive. It’s inevitable. Everybody knows he must be told.

It’s a waiting game, his welfare at the front of his family’s mind, his wellbeing, his mental state. They know his wounds are healing and he had somehow come away from the crash without brain injuries, but they feel they need to take extreme care with the truth.

To tell, or to protect?

So began a liminal period between protection and truth in Vedant’s extraordinary story, a netherworld that lasted three weeks.

When, exactly, should a seriously injured 18-year-old with no brothers or sisters be told his parents are both dead? Is it OK to lie to him, for a little while, until he’s better-placed to find out? Is it better sometimes to withhold the truth?

He was taken from the accident, and when he came to he had stitches in his head, forehead, face, hands and feet, massive blood loss, and a low heart rate.

Teams of colleagues from the petrochemical company had taken over the arrangements at the hospital, the morgue, and also with administrative tasks such as passports, visas and money.

No one said anything, and Vedant was so tranquilised for the pain that he didn’t quite know where he was, or even who he was. There were problems finding the right blood for him, to replace what he’d lost. But he was breathing …

A week or so later, he was cleared to fly back to India; the bodies of his mother and father were on the way there, too, to Vedadora, back home.

By now Anant and Uma had reapplied for visas and been cleared to travel, despite the pandemic.

Vedant was in a wheelchair, still heavily tranquilised, the company paying for the flights and assigning two of his father’s colleagues to go with him as chaperones and carers.

Once home, family members looked after him, but he was still tranquilised and dopey and sleeping most of the day and night. However, Vedant was beginning to figure out that all was not well. The picture forming in his mind was unclear and incomplete.

Ayushi remembers a video call between them around this time, when he was able to talk again. She had seen him before this, on video calls from the hospital with the company people, seeing his injuries and stitches, and also that his hair and beard had grown.

She couldn’t go to Vadadorra to see him yet, because she was busy with family and life matters there that kept her away. She knew he was alive, but she was also scared of the huge challenges ahead.

“All he did that time was keep asking: ‘Where are they? How are they? What is going on? Why am I in India?’,” she says.

“We had to lie and tell him they were in hospital and that he couldn’t talk to them because they would be upset to see his injuries.

“But he was still on such a high dose of medicine that he didn’t know what was happening – he forgets everything and sleeps, for his recovery.”

But the moment must arrive. It’s inevitable. Everybody knows he must be told.

It’s a waiting game, his welfare at the front of his family’s mind, his wellbeing, his mental state. They know his wounds are healing and he had somehow come away from the crash without brain injuries, but they feel they need to take extreme care with the truth.

“I’ve been working with students for more than 20 years and I’ve seen a lot of awful things happen, but Vedant’s situation is probably the worst.”

Vedant had enrolled at Monash a month before the crash. He had done a month’s worth of classes remotely. He won a scholarship for his Year 12 marks.

A fellow Indian student from the course heard the news and told the Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) unit coordinator, Dr Jess Gibbons, who told course administrator Margie Boatman, who told Professor Liz Davis, then the head of the Institute’s Bachelor of Biomedical Sciences program. Jude Little, the manager of student support and engagement at Monash Connect, also quickly became involved.

Tragically, Professor Davis died suddenly just a couple of months into managing Vedant’s case.

All were in touch by now with Uma and Anant.

“Liz and I managed a Zoom with Vedant pretty early on, and we figured out quickly that at that stage he wasn’t well,” says Margie Boatman. “He was insisting even then that he start back studying straight away.”

They suggested he perhaps defer for a semester.

“We had a little cry after that first meeting,” she says. “We were trying to hold back the tears on the call. I’ve been working with students for more than 20 years and I’ve seen a lot of awful things happen, but Vedant’s situation is probably the worst.”

In Hindu tradition, there were 11 days of mourning for Piyush and Mamta in Vadodara, during which time their bodies would be in the house. A couple of days before this was to begin, the moment of truth arrived.

Vedant was staying nearby with relatives. He was put in a car and told he was being taken home. He saw many people outside as they approached. As he was taken inside, they all nodded to him softly. He was put on a bed.

“There were 15 or 20 people in that bedroom with me,” he says. “My grandparents, my cousins, my cousin who is also a doctor, my mother’s sister. They were holding me and stroking me and patting me.”

He was asked if he had thought about his own injuries, and how Piyush and Mamta might have been injured more badly, in the front of the car.

“Are they no more?”

His grandfather nodded with that same softness, and kindness.

Then he lowered his eyes.

The 11 days of ritual began. Mourners came into the house to see Priyush and Mamta’s faces, cleaned up, in repose. Vedant was shown. He moved to a friend’s family house nearby. Everyone, especially his grandfather, agreed that was right.

“My grandfather, he is a very strong man,” Vedant says. “He says we shouldn’t pollute. In India, they even put bodies in the river. So we didn't do that.

“Many people praise my grandfather. He even asked the medical team if we could donate the bodies to medicine, because my mother and father were so young. We couldn’t, because it had been too long since this thing happened to them, but it was much appreciated.”

The house was full of people, and there were Hindu ceremonies and processions in the street because the couple were much-loved and died so young and so suddenly.

Vedant visited the house. His physical injuries were healing, but emotionally he was all over the place, and still tranquilised to a degree. One day he visited and held his mother’s hand, the next day he refused to accept they were dead.

Each day was better, however. After about two weeks, Ayushi put the word out that she wanted to talk to him on the phone. He called her, she answered, and the first thing he said was, ‘How are you?’. Ayushi burst into tears.

Then a few days later, a group took him to a cafe to meet her. He was drowsy and unresponsive and ordered white-sauce pasta with chilled orange juice, not something she had ever known him to do.

“Not even once did he mention his parents during that meeting,” she says.

‘He never wants to trouble anyone’

After another month, he began to talk.

“There’s this thing about Vedant,” Ayushi says. “He never wants to trouble anyone. He wants to make sure everyone around him is fine and comfortable.

“But he started talking to me, telling me exactly how he feels. He talked to a therapist, too, he did reiki. He was low. I wouldn’t say he was suicidal, but he would keep saying, ‘I don't have any reason to live now’.”

Among other things, he was worried he’d never be able to play football again because of his damaged knee ligament. He was worried about money. He carried the weight, Ayushi says, of “losing everything at once”. He was scared he wouldn’t be able to honour them.

She tried to keep him thinking of the future.

“I just kept reminding him of how much his mother wanted him to come to Melbourne and do good in academic stuff, in sports, and explore new cultures and everything. I tried to always make him excited about the next day.

“But,” she says, “I actually didn’t know what to do, because he was always asking me, ‘Why don’t you come to Melbourne, too?’.”

Vedant spoke with Margie Boatman and Jude Little again, and agreed to defer his semester. He needed to figure out his mother and father’s finances, insurance and investments. He was 18, so had no legal guardian.

He decided he would stay in India for a little while, regain his strength, and sort out his financial future.

“I had to do these financial things,” he says. “My dad’s things. He had insurance and bank accounts and all. I had to find his bank accounts, because only Mum would know about them. I had no clue where he had invested. It was very hard for me to gather all this information.”

He went into his father’s email and took note of anything to do with a bank or an investment or insurance, and then he went to each place in person throughout Vadodara to find out more, all day, by public transport, for 10 days, in summer.

“It was very hard for him,” says Ayushi, “but it was something he wanted to do. I’ve seen him cry over this. His father had bank accounts in Saudi Arabia. Vedant wanted to invest the money for his education here in Australia, for his masters, for whatever he needs.”

Ayushi admits now that she feared Vedant might never recover, that he might be “traumatised” forever. But she’s seen him slowly regain strength and, amazingly, find even more.

“He is a warrior,” she says. “He is very strong, and very smart.”

She decided to ditch her California plans and follow Vedant to Melbourne.

“We were very close as friends and then we started dating,” she says. “But I was going to the United States, so we both believed we had no future.”

She had an offer from Monash as well, so she cancelled San Jose, accepted Monash, restructured her student loans, and told Vedant the good news – that she loved him, was in awe of him, and would travel with him for their new life.

“I think If I had left him and gone to the US, I would have felt a void in my heart. I would not have been happy. Even if I achieved some things there, I would always have in my mind that I had hurt a good person.”

Ayushi’s mother gave her blessing. She told her daughter that maybe Vedant wanted her in Melbourne more than she wanted to be in San Jose. Maybe, she said, she had manifested it.

“I’m really happy with the decision I made,” says Ayushi.

She arrived in Melbourne in March last year. Vedant came a month before, in February. He was struggling, she says.

“He was always a guy who would be teasing people and having fun and witty comments and all those things, and when I came I found them missing. But it has all slowly come back.”

He and Ayushi began meditating together.

“I have been practising it since childhood,” she says. “It has helped him. Honestly, I don’t know how I would have faced all this, but I don’t don’t want to be weak in front of Vedant, because that will make him weak as well. So I try to push him and help him the best I can.”

Last year, Vedant became a Monash international student ambassador, and was elected treasurer of the International Student Association at the Clayton campus.

He is now president, and Ayushi is treasurer, and he is about to finish his second year of studies.

This year he invested in and helped promote an Australian tour by a stand-up comedian from Mumbai, Varun Thakur, who performed in Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide, Brisbane and Auckland. There are plans afoot for another tour by another comic next year. Laughter as medicine, but it made for a “hectic” 2023.

“Too hectic,” he says, “but very good.”

His knee ligaments healed up and he is able to coach, referee and play football and go to the gym. He works at a part-time job in Prahran, is studying hard and doing well. He drives, even; he drives a little yellow car to and from work, a long haul. He’s thinking about getting a motorbike. He has his own room at Anant and Uma’s in Tarneit; they have no children, he is theirs, they are his, in a relationship his case worker Jude Little calls “special and wonderful.”

Ms Little has an arts degree with honours in criminology and a postgrad diploma in psychology yet she says the young man from Gujarat taught her important life lessons while she was helping him back-date his deferrals (with special consideration) to meet deadlines and recover.

“He is someone you meet and take with you,” she says. “Someone who stays in your heart because they teach you about life and living. You’ve got to keep going, you’ve got to stay strong and keep believing in your purpose. Trust that people will help get you there, and grab opportunities where you find them.

“He’s an extraordinary human being. I’ve never met anyone who has found so much strength through adversity. He’s lost both his parents at once, he was nearly killed himself, and yet he’s come here and he’s embraced life with full force. He’s making the best of it, he’s representing himself. And he does it all from a place of heart and kindness.”

Vedant says Melbourne is his new start despite living, he says, with a “void” especially when things don’t go well. He says he wants to tell prospective international students that if they are scared to make the leap to go to a place far from home, it’s OK.

“If I can do it, then so can others,” he says.

“I came here and started to feel good,” he says. “I had so many memories attached in India, my mum and my dad. I was around so many people all of the time, and all of those things.

“This is a complete new start. I have my uncle and aunt, and Ayushi, and Jude and Margie, and my friends.

“I feel like things are going uphill for me now.”